By Daniel Van Oudenaren

The short answer: Yes. But also: It depends. Economically, it makes sense for local governments to borrow now, if they’re going to borrow at all. Politically, the case for borrowing is a little less convincing.

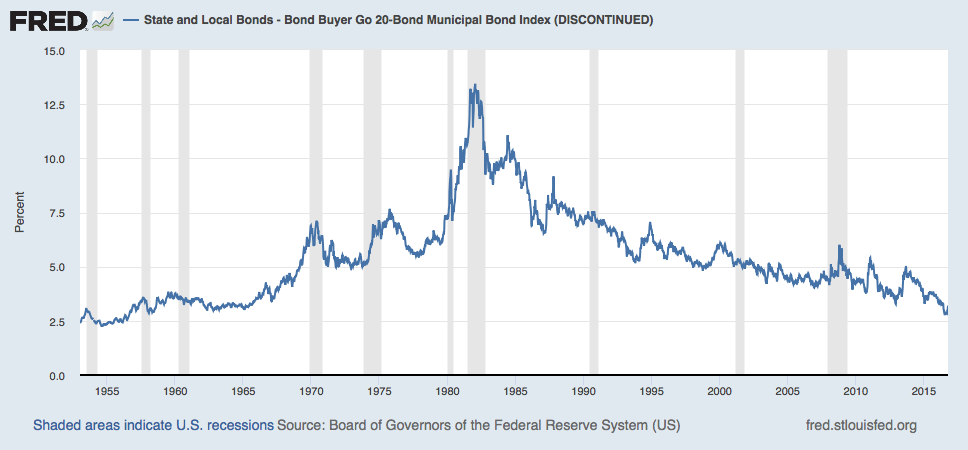

Interest rates are historically low, which makes borrowing cheap. Last week the yield on the Bond Buyer’s Municipal Bond Index hit 2.56%, the lowest since June 1956.

What that means is that investors want municipal bonds, and they want them bad enough to accept a relatively low return on their investment.

For example, Williamson County earlier this month sold $348 million in roads and parks bonds with a rate of 2.32% – barely higher than the 2019 inflation rate of 2.3%.

That’s a very favorable interest rate, especially if the inflation rate stays at about the same level, or rises. Because inflation erodes the value of money over time, the dollars that a debtor gives back 5, 10, or 15 years from now are worth less than their value at that time that they were borrowed.

Williamson County will use that $348 million to build parks and roads in the near term, while deferring repayments on those expenses until those repayments are actually worth less.

For this reason, bond investors tend to demand a higher interest rate than what they expect the inflation rate to be. But a couple of market factors are distorting that typical calculus, leading to favorable conditions for borrowers and less favorable ones for lenders.

Safe Haven Asset

One big reason for lower bond yields is stock market volatility over the past few years. Investors have feared a global manufacturing slowdown and trade tensions with China, Mexico, Canada, and Europe. That generated a “flight to safety” as investors sold stocks and bought bonds, which they perceive as safer investments.

Strong demand is also coupled with limited supply. Municipal-bond issuance slowed in the years after the recession (other than a temporary boost from federal stimulus in 2009 and 2010). In each of the five years from 2011 to 2015, nationwide municipal-bond issuance stagnated below a ceiling of about $150 billion, according to data from Refinitiv.

New issuance rose steadily since then, but last year’s borrowing of $248 billion was still slightly below the pre-recession borrowing level in 2007. So there’s a mismatch between supply and demand, resulting in more favorable conditions for the borrowers.

Effect of the Tax Cut

Another reason for low municipal bond yields is the effects of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Because most kinds of municipal bond are tax-exempt, wealthy households like to invest in them in order to shelter returns from taxation.

The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month, “High-income households looking for tax relief drove record inflows into muni-bond mutual funds last year.” Those inflows push up the face-value price of outstanding bonds, which pushes down their yield. In turn, that lowers the coupon that new issuers are willing to offer.

Global Bond Market

Finally, the bond market globally is pretty out of wack. In Europe and Japan, zero-yield and even negative-yield bonds have become commonplace. Leaving aside the reasons for this, one consequence is to push up the relative value of the dollar as foreign investors seek haven assets in the U.S.

In other words, a Japanese or European investor looks at a 2.32% yield on a bond from a Texas county and thinks it looks pretty tasty compared to the 0% or -1% that he’s going to get at home.

The Need for Infrastructure

Demographically, Texas is booming, which puts strain on infrastructure like public roads, water systems, and schools. Unless we’re just never going to upgrade this infrastructure, then it makes sense to get started sooner rather than later.

Austin voters defeated a billion-dollar road and rail bond in 2014. Now many voters are probably kicking themselves as they sit in stop-and-go traffic every morning.

A new transit proposal will be on the ballot in Austin this November. This time it’s more likely to pass, but now it will be more expensive to implement. Any needed land purchases for rights-of-way will be costlier, and traffic disruption due to construction will be worse today than it would have been in 2014.

So that’s the case for borrowing now rather than later.

Of course, the rising population does boost the tax base, which means that theoretically local governments could invest incrementally over time out of existing budgets, rather than borrowing a lot up front.

But ambitious capital projects are often hard to fund out of annual budgets. And with interest rates so low, it’s practically more economical to borrow and repay later, reaping the rewards of improved infrastructure in the near term while deferring the liability.

Elsewhere, some state and local governments have locked in low rates for as long as 100 years – selling bonds that don’t mature for a century. In September 2019, for example, Rutgers University sold about $300 million of such ‘century bonds.’ Unless there is serious deflation (something that’s been rare in American history), this move is likely to save them a lot of money over time, as compared to borrowing at higher rates later.

The Politics of Borrowing

That’s the market side of the story. Politically, the case for borrowing is less persuasive. Texans are burdened by already high property taxes, which are rising as property values are reassessed.

That makes voters wary about big spending that could hit their wallets later.

Understandably, some voters also might fear what kind of psychological effect such easy money could have on our political class and the body politic more generally. Cheap debt could engender wasteful spending habits, eroding the culture of thrift that many Texans value, conservatives especially.

After all, that’s the situation at the federal level. Many people don’t want to pass on so much debt to their children and grandchildren.

Finally, there’s the divisiveness of the political culture overall. That makes it difficult to agree on what’s a necessary project and what’s not. And it makes it difficult to predict whether debts eventually will be repaid and retired, or will only be added to indefinitely until they’re unsustainable, triggering a default crisis.

Without political consensus, and without clarity of vision, it makes it difficult to invest successfully in big economic projects. The interstate highway system, the Moon Shot, and the MD Anderson Cancer Institute never would have gotten off the ground if there hadn’t been widespread consensus.

In Texas, starting small may be politically more palatable than swinging for a home run. As transit advocates learned the hard way in Nashville in 2018 – where a huge $5.4 billion transit plan was defeated – it can be a harder fall down when you’re aiming to fly high.