EDITORIAL

The eleven Democrats on the Austin City Council this past week gift wrapped the November 2020 election and handed it to Texas Republicans on a silver platter.

A vote to slash 34% of the city’s police budget is controversial within their own party, alienates local business interests, and has stoked furor throughout the Lone Star State. The move threatens to demoralize the police and undermine public safety at a time when homicides, assaults, and deadly road accidents are on the rise.

City Hall insiders and their apologists in the media have been quick to point out that the immediate cuts are only for about $20 million, or 5% of the police budget, while larger cuts will come later, mostly stemming from transferring programs like Victims Services from the police department to other city departments – not from outright eliminating officers and programs.

But that misses the point. Council members wanted to put on a show, and they got one. Their budget even calls for booting the police from their own downtown headquarters and moving them into other city buildings.

It’s a costly and grandiose gesture, and while it might pacify far-left elements in Austin, it will alienate Texans elsewhere, dooming Democratic efforts to retake the Texas House, and potentially reversing Democratic gains among Hispanics, who are disproportionately affected by crime and constitute about 40% of the state’s population.

Following a gain of 12 seats in the Texas House in 2018, Texas Democrats were in striking distance of controlling the chamber, which would allow them to block Republican gerrymandering during redistricting in 2021.

They also were in a position to exploit Republican vulnerabilities over their mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic, and they aimed to make Donald Trump play defense in Texas, where he won only 27% of the Republican primary votes in 2016.

Longer term, Texas Democrats are looking to continue to expand in growing suburbs that form the battleground between the deep-red rural parts of the state and the deep-blue cities.

All of these efforts now are in jeopardy because of anti-police rhetoric out of deep-blue cities like Austin, Portland, and Seattle. Substantively, such attacks on the police also undermine Democratic efforts on gun safety and prisons reform, neither of which will gain any traction if voters feel insecure in their own neighborhoods.

In the 1960s, when Republicans first started gaining ground in Texas, they had to work hard to paint Democrats as “weak on crime” liberals. That effort, which eventually succeeded, ended a century of Democratic power in the Lone Star State, and launched Ronald Reagan into the White House, as well as two Texans, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush.

Now, the GOP doesn’t even have to call names; the Democrats are doing it to themselves. As the saying goes, those who do not remember the past are doomed to repeat it.

100 Years of Democratic Power – And How It Was Lost

Between 1876 and 1972, Texans chose the Republican candidate in a presidential election only twice, and both times that was the war hero Dwight Eisenhower. They voted four times for the architect of the New Deal, Franklin Roosevelt, three times giving him over 80% of their votes.

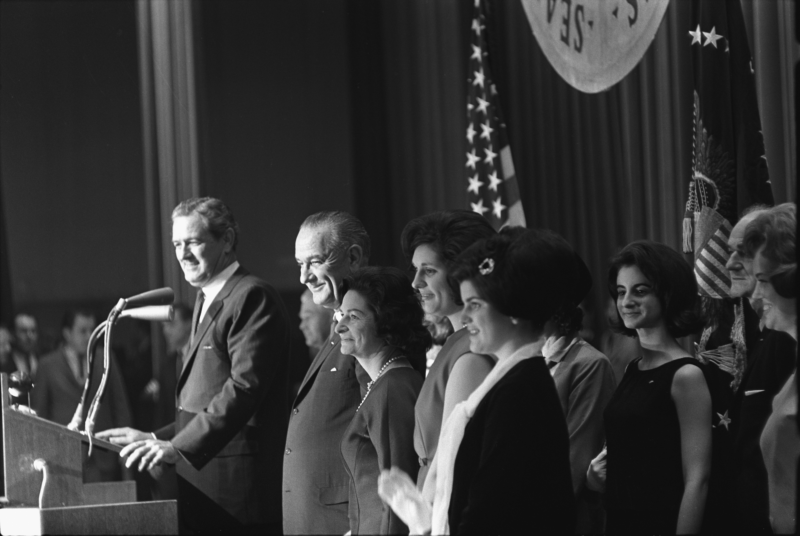

Texans voted for Roosevelt’s vice president and successor, Harry Truman, and they even voted for a New Englander, John Kennedy, over Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. Then they backed their own man, Lyndon Johnson, with 63% of their votes in the 1964 election.

But something began to change during the Johnson years as the Democratic party tore itself apart over Vietnam, the counterculture, and civil rights. Texans watching the nightly news in their living rooms increasingly saw images of protests, urban riots, and reports of drug use and rising crime. They worried about communism overseas and radicalism within the Democratic Party that they had long supported.

After Johnson dropped out of the 1968 election, Texans showed less enthusiasm for his Democratic successor, Hubert Humphrey, but still gave him a plurality of their votes, passing on Richard Nixon for a second time. (A third-party candidate, the segregationist George Wallace, won only 19% of the votes in Texas, a far lower showing than in Southern states, five of which he won outright).

During the next four years of the Nixon administration, the country was seized by unrest. Protests against the Vietnam War intensified. There were unexplained bombings, acts of riot, and widespread disruptions on college campuses.

Conservative Texas Democrats began to feel increasingly at odds with their own national party. They began to defect; John Connally, the Texas governor from 1963 to 1969, who had been wounded by the same bullet that killed Kennedy in Dallas, took a cabinet post in the Nixon administration. He also headed a campaign group, “Democrats for Nixon,” that opposed the Democratic nominee, George McGovern, portraying him as weak on defense and crime. Millions of Texas Democrats followed Connally’s lead.

McGovern, sensing he was vulnerable on crime, sought belatedly to show that he could be tough. In an Oct. 3, 1972 address, he “promised to make eradication of crime and drug abuse ‘the No. 1 domestic priority of my administration,’” the New York Times reported. The Democratic candidate called for federal financial aid to crime-troubled cities that would be “focused on increasing the number of foot patrolmen.”

But the damage had been done. McGovern lost Texas to Nixon 33% to 66%. Texans would give Democrats one last chance – narrowly choosing Jimmy Carter in 1976 – but ever since no Democrat has won the presidential election in Texas. In fact, since 1994, Democrats haven’t even won a statewide election for a post like attorney general or general land commissioner.

Texans venerate lawmen like Sheriffs and Rangers – they’re an iconic part of Texas identity.

Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, Texas got redder and redder. The “weak on crime” label became one that Democrats couldn’t shake; Michael Dukakis in 1988 famously was attacked for his “revolving door” prison policy, after he had vetoed a bill to stop furloughs for murderers.

There were other reasons, of course, why Democrats lost elections in Texas. But the law-and-order message was a strong part of it. It resonates so strongly in the Lone Star State because frontier lawlessness is such an important part of the state’s collective memory. In the 19th century, Texas struggled to overcome lawlessness and establish a working justice system. That’s why Texans still honor the badge and venerate lawmen like Sheriffs and Rangers.

There were injustices along the way – historians have documented some atrocities perpetrated by the Texas Rangers, for example – but on the whole, that hasn’t changed public opinion, and law officers remain an iconic part of Texas identity, not only in film and in popular culture, but also in Texans’ political consciousness.

By launching a direct assault on that identity, Austin Democrats on City Council are playing with fire. Their budget cuts won’t turn Austin into a lawless town overnight, but they could undermine security in the longer term, and they’ll have political repercussions for a long time to come.