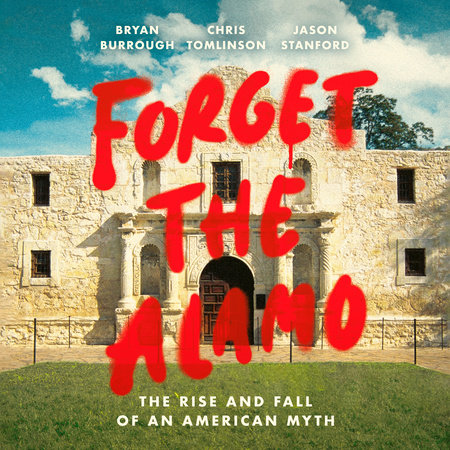

In January 1846, President James Polk ordered Zachary Taylor to advance troops to a remote part of Texas still unequivocally claimed by Mexico; the goal was to provoke an attack. In June 2021, authors Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford released Forget the Alamo to do the same.

The book purports to be a debunking of the traditional Texas history of the 1836 Alamo siege — a version that the authors refer to as the Heroic Anglo Narrative. But the authors also never tire of goading the usual suspects of today’s Texas politics. They line up George P. Bush, Dan Patrick and Allen West for vituperative jibes and good old fashioned Lone Star gossip. The irreverent journalistic chapters occupy approximately the last third of the book.

The authors recount the Texas General Land Office’s ongoing effort to build a multi-million dollar Alamo museum to house a massive collection of Alamo memorabilia donated to the state by retired pop star Phil Collins. As it turns out, the authenticity of these items is suspect, to say the least. We meet Bruce Winders, a sometimes hapless but always committed historian of the Texas Revolution, as he seeks to verify some of Alamo collections’ greatest hits:

“Winders turned his attention to the four books of receipts Collins furnished, laying out where he had acquired his items as well as their provenance … What Winders read left him greatly concerned. ‘It was kind of painful because I was finding things that were just somewhat disturbing, you know, this isn’t right…. What I saw were items that said they were of this type; they could’ve been at the Alamo.’ But again and again Winders leafed through the documentation and found no proof.”

This is what the book does best: It encourages the reader to take a more critical look at the state’s policies toward the Alamo. Before reading Forget the Alamo, I probably would have been marginally in favor of more infrastructure around the old San Antonio mission, but I came away believing that the Alamo is all right as is. Better that it be a park than a theme park.

However, Forget the Alamo has attracted more attention for its treatment of the past than its insights about the present. A book event with the authors at the Bullock History Museum was controversially canceled July 1. In the media blitz that followed, the word “facts” was evoked more than facts themselves. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, for instance, called the book a “fact free re-writing of Texas history,” without explaining which “facts” he took issue with. And the authors themselves call upon the authority of facts as much as anyone else. In their introduction, they write: “We love facts, especially the facts of history, and we don’t believe knowing the truth about Texas history makes the state any less unique or important.”

So far so good. But facts aren’t enough to carry a history. Writers also decide what facts matter and what conclusions to draw. The facts selected are meant to be provocative: Stephen Austin believed that his colonies would fail without slavery, Jim Bowie was a human trafficker, William Travis probably had syphilis, etc. It’s hard to argue that they aren’t true, but facts less consistent with the authors’ narrative are either omitted or banished to the endnotes (where most readers will never look).

The characters who populate Texas’s founding were much more complicated than the authors imply: Sam Houston abandoned White society twice to live among the Cherokees, a point that should be fascinating to anyone interested in the racial complexity of the early frontier. But the authors only mention this in passing. Similarly, the authors repeatedly describe Crockett as a failed politician, but they don’t seem to care that he was a brave one too, willing to go against the opinion of his constituency and oppose the shameful removal of the Cherokee.

It’s too much to expect the authors to provide a full biography for all of their subjects. But their cavalier tipping of sacred cows doesn’t provide the mature assessment that their subject matter deserves. A more nuanced approach would acknowledge that America’s frontiers were both the staging grounds for racial violence and myopia but also laboratories for reshaping social norms. It wasn’t a coincidence that frontiersmen like Sam Houston, Jim Bowie, and Deaf Smith would marry across ethnic lines.

“The authors’ cavalier tipping of sacred cows doesn’t provide the mature assessment that their subject matter deserves.”

In chronicling the history of Texas, the authors put forward Frederick Jackson Turner’s well-known frontier thesis as the root of what is wrong with traditional Texas histories. They write, “Turner argued that the Anglo conquest of the American West generated a spirit of freedom, democracy and egalitarianism and created a unique American culture. This was history by, for and about the white man; Native Americans, Black people, and Latinos were marginal characters at best, two-legged buffalo at worst.”

There are intelligent ways to critique Turner’s frontier thesis. The one presented above is not among them. While Turner’s views may suffer from the shortsightedness and hubris of the late 19th century academic establishment, his thesis that the frontier facilitated more opportunities for liberty and equality would have made sense to the Latter Day Saints of Utah, the Buffalo Soldiers of Arizona, or the immigrants to Texas in the pre-revolution years.

Anglo Texas lacked the social stratification of Eastern cities like Philadelphia or Boston, despite Stephen Austin’s best efforts to establish a bona fide planter class. Many American immigrants to Texas were debt refugees like William Travis or swindlers like Jim Bowie. There’s little doubt that these low-born Americans were afforded more opportunities on the frontier than they would have had in the interior, even if one might take issue with the second chances afforded to some of them.

Turner’s account could use an update, one that acknowledges that Comancheria and the Mexican Republic had frontiers too. That isn’t what the authors want, though. In opposition to conservative historians, who would have us understand the Alamo as Bunker Hill 2.0, Forget the Alamo posits that the Texas Revolution was no more justified than the Lost Cause. Neither of these extremes is correct.

The Texas uprising was a provincial rebellion within a larger Mexican civil war against an authoritarian government. It also represented the violent periphery of a Jacksonian revolution that, within the United States, was usually waged with ballots. It was a revolution that upended the older aristocratic pretensions of both the Federalists and Jeffersonians. It didn’t overturn all of the illiberal institutions of American society, including slavery and racism (which it may even have extended further). But much of American society emerged from the age of Jackson more democratic and economically equal.

A narrative like this is probably too subtle for 7th graders, which is unfortunately the grade in which most Texas students learn about the Alamo. Forget the Alamo offers a much simpler view of a complicated period. Hopefully it won’t end up becoming the primary narrative taught in schools. That said, Texans shouldn’t fear students reading a controversial book. The challenge these days is getting young people to read any history at all.

Also by James Banks:

2 comments

Mr. Banks tries mightily in this review to make the authors seem unwilling to see other forces at work in the Texas rebellion.

The hard truth is that Texas was established as a slave state. The driving force behind that Anglo settlers was maintains slavery. All other reasons are secondary.

Less then 5% of Texans owned slaves. Corporate plantations came in from the east after texas joined the union to take advantage of the surplus of land but Most peaple who moved to texas when it belonged to Mexico, or Spain like my family, did so to become Cattle farmers and mule ranchers on the frontier away from NY, we’re irish and Native. Half the peaple who fought in the Mexican Civil for Texas success were Tejano and or Indian and most Texans even to this day are Hispanic or Indian, and even most the white peaple are mixed especially if they have roots that go back to the Spanish land grant when Spain need a buffer state for Comancheria and were inviting anglo-irish-german settlers to basically be arrow sponges